By Bex Hong Hurwitz, Tiny Gigantic

Over the past months, technical research into privacy and security concerns with Zoom and Zoom’s actions in response have led activists and organizers to reassess whether Zoom is safe for organizing. Questions about trust, safety and privacy that activists and organizers are asking about when using Zoom mirror questions we have to ask about any communication technology. If you are making decisions with other organizers about choosing safer, values-aligned technologies for activism, this post is for you.

In this post, we will address:

- Switching tools is a process; tips for change management

- Assessing trust and risk in; service/platform hosts, data collection, legal privacy protections, software code, and end-to-end encryption

- Getting the goods through collective action

Switching tools is a process

Switching tools is a process, not always a quick and easy decision or act. In conversation with activists, they have shared they would like to switch but are still using Zoom. Some reasons include: familiarity with it and part of their process of making space online as hosts and participants;having pre-paid accounts as individuals and groups ; Zoom’s accessibility services such as simultaneous interpretation and closed captioning work well.

As we move towards using more values-aligned and safer technologies, we will need to change some of the tools we use and some of our ways of using them.

Some questions to ask when managing change with a group of people:

- Identify change stewards. Within your community, who should be a part of stewarding this change? How inclusive does your community want this process to be?

- Communicate about the need to switch. What information do you need to share so that people understand the need for change?

- Research and test. In order to know if a tool will fit your particular needs, it’s important to test. It’s also helpful in supporting others to have a few people who have been part of a testing process who can respond to questions and lead adoption.

- Support and training. How do the people you are organizing with learn best? What resources do people need to learn and change(examples could include written resources, hands-on trainings, check-ins and space for feedback and discussion)

Assessing Trust and Risk

When we are using software and services made by and run by other people, here are some questions to ask when assessing risks and trust:

- Who runs this service? What do they say their values are?

- How do they respond, and take accountability, when an incident or issue arises?

- Who do they say they are serving? Identify who it is built for and who it is safe for?

- Are there examples of the service standing up for activists and privacy?

- Are there examples of the service harming activists?

- Is the code open source? Has it been reviewed by an “independent auditor”?

- Is communication end-to-end encrypted? Has it been reviewed?

- How much and what information is gathered by the host on who is using the tool?

- Where is the company based and where is the data stored?

Trusting the host with our privacy and safety in response to surveillance

A host of a service is responsible for decisions about the user information it collects and stores. We need to look for technology hosts that say they prioritize privacy and, whenever possible, hosts that say they are committed to our particular needs for privacy and freedom from surveillance.

Data stored by a host is susceptible to corporate and state surveillance and legal investigations. The kind of information that video conferencing hosts gather and store about calls varies widely. For example, Zoom collects a wide range of information about participants. This includes account information if you’re logged in, IP addresses of computers joining the call, and sometimes call content including video and chat recording. Jitsi, in contrast, doesn’t require an account to use. A Jitsi host can change default settings, but by default, Jitsi does not store meeting information like video, chat, information about participants and once the last person has left a room, the meeting is forgotten.

It is often unsafe for activists to leave records of individuals who joined a meeting and word-for-word recordings. Video conferencing tools do not need to collect and store all of this data. We can look for tools that are designed to store as little information as possible about meetings and participants.

When you are reviewing a service, you can generally find information about the data it collects and stores in privacy, legal, and security statements available on websites. For example, read more about the information that Signal makes and retains about users here: https://signal.org/legal/

Some protections from privacy laws and legal jurisdiction

Our data can be safer if we use a service that is based in and stores data in a country where privacy laws are strong and our organizing is less at risk of surveillance from that state. At this moment, the privacy laws in the European Union (EU), updated under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), are among the strongest in the world and attempt to make service providers more accountable to users in the ways they make and employ data about users. Ideally, this means that an EU based service is storing less data about its users and we have more control over how that data is used and when it is deleted. Additionally, corporate technology companies based in the U.S. are known for participating in National Security Administration’s PRISM surveillance program which can be used to demand that Internet companies turn over user information to the federal government, but an EU based company would be outside of U.S. jurisdiction and this particular program.

“End-to-end” encryption to resist surveillance

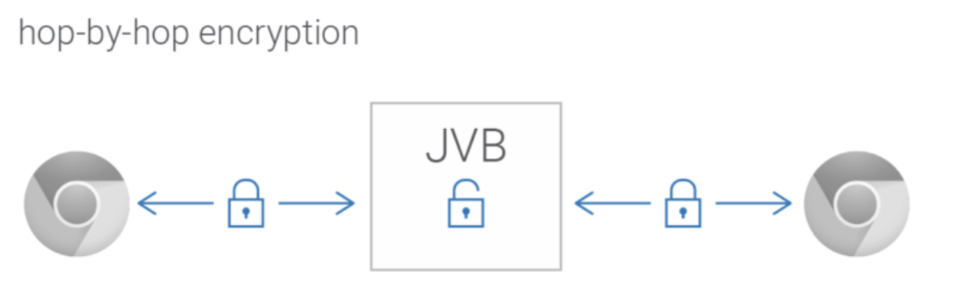

Zoom advertised its software as “end-to-end encrypted” but through research by University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab and an investigation by the Intercept, we learned that Zoom was not providing end-to-end encryption, but rather, hop-by-hop encryption.

When we are talking about communication, we use the term “end-to-end encrypted” to describe an encrypted (coded), message that can only be decrypted (decoded) by the sender and the recipient of that message.

Imagine sending a message in a locked box to someone and only you and the person have the key for the box. The message may pass through many hands at a post office and along the sorting and delivery processes, but no one along the way can read it.

When activists are communicating we need services that are end-to-end encrypted to ensure privacy from corporate and government surveillance. Video calls are not often end-to-end encrypted. Zoom’s representation that its software was end-to-end encrypted, is a reason why we initially chose and recommended Zoom.

Most video conferencing is hop-by-hop encrypted. Video is encrypted between a person on the call and the service provider. This keeps the call from being eavesdropped on while it is in progress and is a critical requirement for anyone having a conversation. With hop-by-hop encrypted services, the service provider decrypts the data it receives from each participant to send it out to other participants, we need to trust the host deeply, both to not surveil the content for purposes like sales and to not allow state surveillance. Zoom has said publicly that it never built mechanisms for governments to view decrypted content. But we do know that Zoom spied on users on behalf of governments and took action by closing accounts of activists, so it’s hard to trust Zoom’s word.

Trusting the code and using open source software

How do we know if we can trust the way software is written? Software is made of code, sometimes called “source code” or “source.” Open source software makes its code viewable so that people can contribute to it and reviewable for security concerns. We should look for software that has been reviewed by an independent reviewer and look for software developers who share those reviews, sometimes called “audits.”

Beyond code, the open source software movement envisions a collaborative technology development process and collective stewardship of technologies. The movement serves as an important countervision to corporate ownership and management of software and internet services that is more aligned with social movement values of interconnectedness and cooperation.

MayFirst Movement Technology is a non-profit organization that works to build social movement through “Internet work” that is member-run and uses only open source software and runs services for hosting websites, email, and other communication services like Jitsi video conferencing, Mumble voice conferencing and NextCloud for document collaboration. Read more about MayFirst here: https://mayfirst.coop/en/

Collective action gets the goods

There might be times when we have to use and choose technologies that are not aligned with our values and our needs for privacy and safety from surveillance. We can join collective campaigns to push our software developers, hosts, and privacy laws to make digital communication safer for activists and organizers.

For continued practice in holding platforms accountable see this post to learn more about the campaigns that compelled Zoom to improve its services for activists: Safer video conferencing through public awareness and collective action.